An essay commissioned by Winnipeg Arts Council, October 2022

Hannah Godfrey (hannah_g)

I carry an image in my memory of a place that is real but does not exist. It’s a cave, a sandstone-ish cave and I don’t know how big it is. It’s dry, hospitable, and its walls are uneven, full of nooks, cracks, scoops, and sheers of many sizes. Ultimately, it’s a cave that will not ever be fully known, some of its surfaces will remain forever in the shadows and that’s no bad thing; it’s not always for the good to have absolutely everything in sight. This cave is, of course, within me. When I speak or write about it my hands go to my chest and stomach, so I think that’s where it lives.

I first became aware of this cave at the Fort Whyte Nature Centre. I was with my friend, Azzy. We’d gone there a few weeks after we’d stopped dating and started our friendship. She asked me how I felt about our relationship. The cave swam into my mind as I tried to put into words how she made me feel. As I described it to her the cave grew into a real place, I could see it so clearly. She had been like a lantern held up to reveal beautiful peachy-almond colours and depths I hadn’t seen before. To experience that had been wonderful, a true marvel.

The cave’s illumination is not limited to friendship, romance, or family. Fleeting exchanges—glances, gestures, brief words—those lights may be remembered for years. And it isn’t limited to people either, places can be lanterns too.

For months last year, I walked along the stretch of the Assiniboine River that flows through downtown Winnipeg. Close to the water, I watched seeds sprout into saplings that grew optimistically. I began to recognise the people I passed each morning. Most days I’d see the silver slip of a fish as it broke the water’s surface with a tight flip, and once I’m sure I saw an otter floating on her back. I enjoyed the rogue gardening of a lady who planted cosmos and sunflowers near some unused ornate steps where she hauled water from the river in large ice cream pails. We didn’t share a language but we shared delight in her flowers’ progress. It’s only looking back that I understand that the river and all of the activity around it were lanterns, surprising with me with new patterns of light and movement.

The walks stopped this year with the prolonged flooding of the river path. I made a few half-hearted attempts to reroute through the parks perched atop its banks. In one of these parks is a reflecting pool but in the late spring it was dry with only grit and litter rustling around it. Near one end is a plinth, an empty rectangular cube about a metre high. One morning when passing by I saw a grimy duvet bundled on top of it. I continued for a few steps before the realisation sunk in that there was a person in there. I backtracked and watched for small movements that would tell me the being in the bundle was ok. It remained perfectly still. After a few minutes, I asked softly, “Hallo? Are you alright?” A head with short brown tousled hair suddenly appeared and a face with barely open eyes nodded at me and gave me a sweet, sleepy smile, the kind that’s usually only seen by a lover or a mother.

A lot has changed for me this year, although the river is presently at its more usual level. Maybe the changes are why the cave and lanterns have been in my thoughts and conversations more—it’s an evocative way of describing the effect that people, places, and experiences have on us; as well as their absence. We illuminate different aspects of each other: giddying and gorgeous, it can happen with a new friend or falling in love or visiting somewhere new. The honeylight soaks our stone and illuminates the depth and colour and shapes within us that in turn reflect back onto the lantern bearer. We find ourselves capable of great things, of experiencing the fullest sensations of life, of understanding ourselves in a way different to the one we are habituated to. Amazing, humbling gift of fullness and joy.

From the beginning of our lives we encounter lanterns. It’s not simple at all. For unlucky folks, the lanterns bore down too harshly or cast more shadows than light. I was very lucky. I had a big, beautiful, steadfast one shining on me with an unceasing sunny light as soon as I popped into the world. My mum filled me with such golden love that the walls of my cave are forever glowing with it.

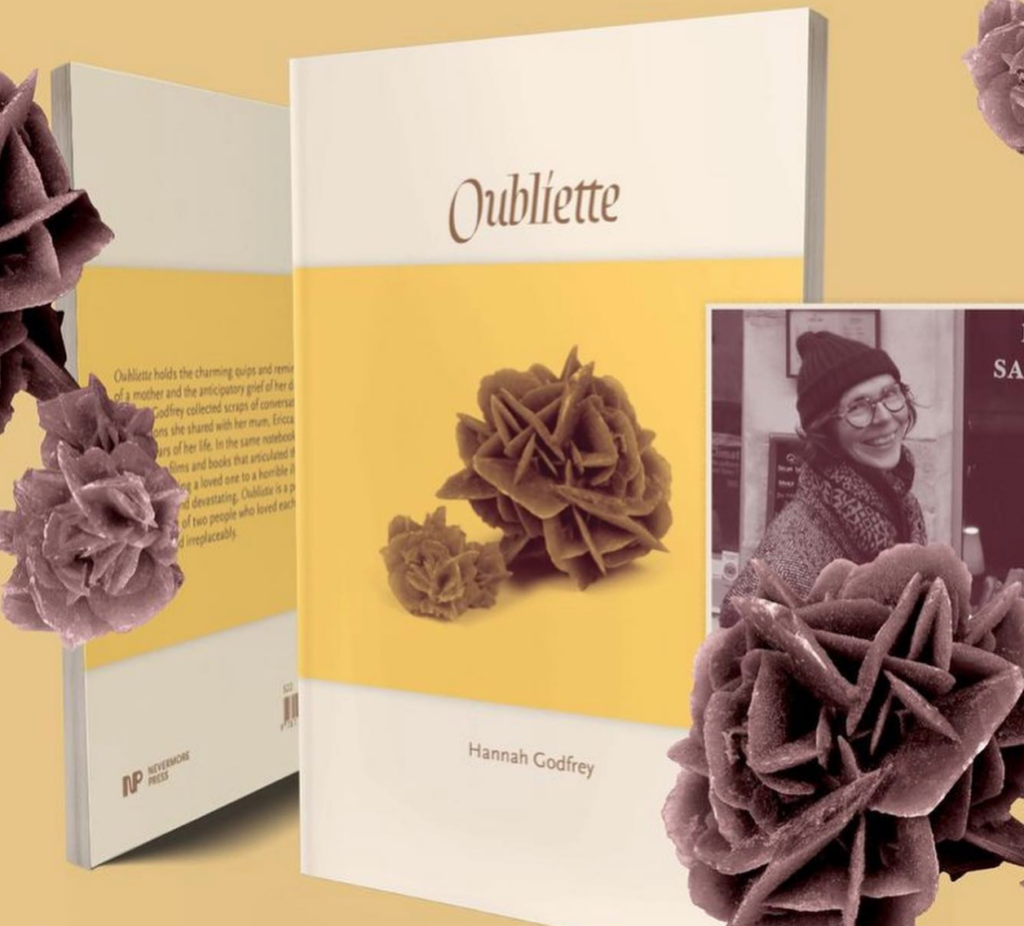

My mum is one the greatest loves of my life and I was one of hers. With her death, the quality of her light within me has changed. Although it is still there, I have to concentrate and close my eyes to feel it instead of giving her a call and hearing her talk. I know her light will always be within me but I miss her gentle lantern, the me-with-her. I miss her so much.

When I reached my home in the UK, I learned she had died before I’d even boarded my flight and terrible mourning fell upon me like a curtain made of treacle. As days passed among the loving lanterns of my family, I was barely aware of some other tiny points of light in the overwhelming darkness that cloaked the future, but by the end of two weeks there was a scattering of persistent white pinpricks poking through. The celebration of my lovely mum’s life took place in the English countryside with those who loved her so very, very much and then—I was back on a flight crossing the gloomy Atlantic again, bound for my other home in Winnipeg, the home where I live.

This city, where many of those tiny, powerful lights twinkled from across thousands of silent miles grew into a quiet chorus of mismatched lanterns held by kind, steady hands, that have been helping me find myself again.